It’s the weekend, when I like to dig through my archives of reviews and shed some additional light on a worthy book. I haven’t done this for a while because, as some of you know, there’s been other things on my mind.

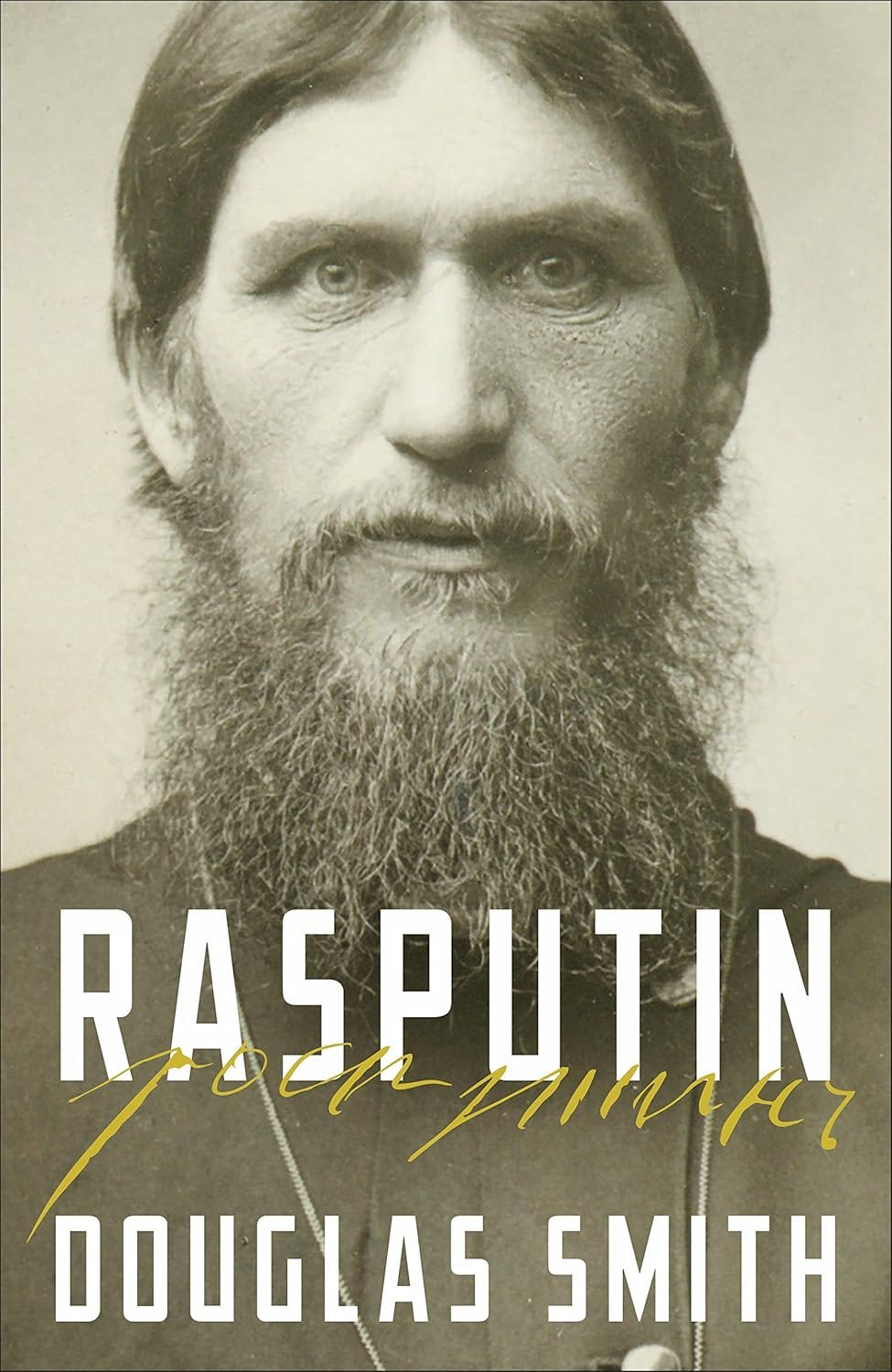

This week I’m featuring Douglas Smith’s Rasputin: Faith, Power and the Twilight of the Romanovs, published in 2016 by Macmillan. It’s a revisionist biography, and that’s quite a challenge with a subject like Rasputin, given that there’s so much myth that surrounds the man. I was drawn to this book because I’ll shortly have to start reading Anthony Beevor’s biography of Rasputin, which will be published next year. Since I’ve never read a bad book by Beevor, it will be interesting to compare it to Smith’s very impressive study. Then again, I suppose it’s difficult to write a boring book about the mad monk — there’s so much to amaze the reader.

Grigory Rasputin was a pervert, predator, drunkard, glutton, charlatan, paedophile, rapist, rogue, spy, and traitor. His sexual appetite was insatiable, his stamina prodigious, his prowess unparalleled, his equipment colossal. He was a homosexual and a homophobe, an anti-Semite and Jew-lover. Rasputin was the ‘holy devil’, destroyer of Russia.

Or so they said.

Douglas Smith begins this impressive biography of Rasputin by rubbishing almost everything previously written, stripping away a century of myth, fabrication, gossip and lie. ‘The thing that made him such an extraordinary and powerful figure’, Smith writes, ‘was less what he was doing and more what everyone thought he was doing.’ The ‘diseased Zeitgeist’ of the early 1900s created this man who was either angel of God or Devil’s servant. ‘During his … lifetime, Rasputin stopped being a man and became the haunting personification of a terrifying era.’

Smith’s intention is not to rehabilitate Rasputin, but rather to tease out the tiny facts hidden within a haystack of lies. This huge task requires the skills of a detective and the patience of a saint. As the symbolist poet Alexander Blok remarked of the dying days of the Romanovs: ‘Rasputin is everything, Rasputin is everywhere.’ Stories about him sold papers – they grew more sensational with every telling. Journalists referred to a disease called ‘Rasputiniana’: ‘A man catches this filth and can’t get rid of it for years.’ Keen to contain the disease, people hung signs in their houses: ‘Rasputin is Not Discussed Here’.

To many, Rasputin seemed a monk on the make. Smith, however, feels that his religious devotion was beyond dispute. In 1897, at the age of 28, he began an extended pilgrimage, walking thirty miles a day in search of grace. On the road, he developed a reputation as a mystic, offering spiritual guidance and the occasional miracle. He developed an ability to read people, to see inside their souls. Instead of fire and brimstone, he provided empathy and warmth. His message was simple: ‘You need love.’ Few could resist his torrent of love.

Rasputin’s love wasn’t simply spiritual; it was physical. ‘I cannot do a thing without caresses’, he confessed, ‘because one gets to know the soul through the body.’ Communicating God’s grace meant touching those in need, even bathing with them. ‘I have been sent to you by the Lord God’, he would say, ‘That is why everyone should love me more than they love anyone else in the world.’

Like a certain someone, he would immediately start kissing a woman on first meeting her. Most thought his advances ‘chaste and pure’ -- but some inevitably found him creepy. Anna Sederkholm, the wife of a Guards officer, once shared a sleeper compartment with Rasputin on a long train journey. Her friend Yelena joined Rasputin in the bunk above, where they discovered ‘religious ecstasy’. Later that night, Rasputin snuggled up to Anna. He could not understand why she rejected his advances. Who in the world would spurn the love of God?

In 1904, Rasputin’s pilgrimage took him to St Petersburg. Within a year, he rose from the very bottom of Russian society to the very top – he became friend and confidante to the royal family. His popularity owes much to the fascination for all things mystical during those turbulent times. Mediums, clairvoyants and savants did a roaring trade. There was, for instance, the Mysterious Dog Jack who could guess one’s age and the amount of money in one’s pocket. The holy fool Mitya ‘The Nasal Voice’ Kozelsky would grunt unintelligible prophecies which his minder Elpidifor would interpret in a manner calculated to please the Tsar. No wonder, then, that Rasputin was like a rock star. In stilted Petersburg society, his crude peasant ways increased his charm. Oh, look, he wipes his mouth with his sleeve. He’s so authentic.

Rasputin met the royal couple for the first time in November 1905. The Tsar was impressed, the Tsarina smitten. Rasputin’s obsession with the Devil, his preoccupation with suffering, and his fondness for self-flagellation (‘hit yourself only when nobody is around’) resonated with Alexandra. ‘Outside her immediate family’, writes Smith, ‘Rasputin was the only man who managed not to fall short of the empress’s impossibly high standards.’ Nicholas was blind to his wife’s obsession, and too weak in any case to oppose it. ‘The Tsar is an angel’, Alexandra’s brother once remarked, ‘but he doesn’t know how to deal with her. What she needs is a superior will, which can dominate and bridle her.’ Rasputin had will aplenty.

Before long, he was a regular visitor. His fondness for touching was apparently not an obstacle to his spending time alone with the children in their nursery. Contrary to popular myth, the royal family’s dependence on Rasputin was not solely due to his magical ability to cure their haemophilic son Alexei. Smith shows that he was offering advice on matters of state long before he performed any ‘miracles’. But those miracles did cement the relationship.

The people began to talk. Who was this Siberian peasant that was so often at the palace? The police and Duma investigated. A leaked letter told of Alexandra’s longing to ‘fall asleep forever … in your embrace’. Blind to the consequences of her actions, she could not understand why anyone would think her relationship sordid. In the spring of 1915, gossip circulated about a drunken Rasputin bragging of sex with the Empress. He supposedly dropped his trousers and pulled out his penis in order to demonstrate the source of his power over her.

The story was almost certainly fabricated, but, as Smith argues, it demonstrates the desperation to destroy Rasputin. Russia, it must be remembered, was a juggernaut beyond control. Rasputin became the convenient scapegoat for every disaster – military defeat, famine, political unrest. In fact, he had advised Nicholas against entering the war and had urged him to distribute food. Smith recklessly speculates on the long-term consequences if only the Tsar had heeded his advice. A group of Russian patriots, however, saw only a Tsar in thrall to a mad monk. He had to go. The circumstances of Rasputin’s assassination are as muddled as every other aspect of his life. A story circulated that he had been fed small cakes laced with poison. But wait, his daughter said, that can’t be. He didn’t like sweets. (The details of just how hard it proved to kill Rasputin is a story for another day.)

This book is longer than it needs to be – detail sometimes impedes the drama. Deconstructing all those myths is a complicated, sometimes tedious, process. On the whole, however, this is a fascinating, often entertaining, biography. One has to admire Smith’s determination to root out the truth. That said, disproving ninety-five percent of the Rasputin myths still leaves behind a thoroughly creepy man. The remaining five per cent that seems to be true was enough to make my skin crawl.

In the end, Rasputin looks a lot like the character with whom we began. He was a sex maniac. He did exercise enormous influence over the Romanov family. But he was not an evil Svengali. He was not, as rumours suggested, a cynical manipulator who ‘hides his depravity behind an aura of blasphemous religiosity’. His greatest strength was his self-belief. Rasputin really did think that his caresses carried the touch of God. Those he touched often believed he was God. In a way, that makes him even scarier than I once thought.

fascinating

Another example of a malignant narcissist (among many diagnoses) who was able to use the power of suggestion to manipulate feeble-minded people.